Life in the FAST Lane

As someone born in the middle of Generation Z, with a lot of weird hobbies, I have a bit of a unique perspective on video games that I like to think I'm very lucky to have. We're some of the last people to have the kind of opportunities to experience what gaming meant before games as a service completely took over, and for computer nerds it was also probably one of the last times we got to grow up knowing what it was like for every piece of gaming hardware to bring something unique to the table. This is something I think about quite a lot, and I want to rant a little bit about one of my most memorable gaming experiences and the influence it has on my programming and design work today.

Leaving Luck to the Heavens

I was the resident Nintendo kid growing up. Going into the 8th generation of home consoles when everyone started getting obsessed with smartphones, and when nobody that I knew cared about owning a Nintendo console unless they were poor or only casually interested in gaming, I was a bit of an oddball. I was all over the Wii U the moment it was announced, and begged to have one for Christmas as soon as it was out. The Wii U utterly flopped, but it was the last good living room hardware Nintendo released in my opinion. I didn't care that it was slower than its competition, and I still don't. The games I had access to were good, they ran good, and the consoles themselves always felt special to me even if there were obvious shortcomings, knowing that most home consoles by this point were trying to double as media centers. You could tell that the people designing the hardware were having fun with it from the beginning, particularly with the design of the controllers and peripherals and the opportunities they opened up for game designers.

The Nintendo Switch was the opposite of the Wii U. It did everything right commercially, but as a console it was really boring. Practical, yes, but if you're a Nintendo fanboy in the 2010s, practical is not what you buy a console for.

The Switch put Nintendo into a position where they were too big to fail, and stopped playing to their strengths. The gimmick of the Switch was nothing but a cheap and shallow convenience. Yes, it is nice to have the same console you use at home also be your handheld, but that was the only new thing the Switch offered. To the average console gamer, what the Switch gave up compared to its predecessors was unimportant, but to me the Switch always felt rushed and very uninspired as a result.

Being 12 (really showing my youth here) and finally having some semblance of financial autonomy, the Switch was the first console I really considered getting on launch day. But, I backed out merely the day before launch and decided to wait another year following many reports of poor quality control. To this day Nintendo still is trying to gaslight people into thinking their controllers aren't broken, and of course all the other OEMs follow suit! Buy more joycons! Who cares about e-waste??

After eagarly keeping an eye on the "NX" for the entirety of 2016, when the console was finally out I really did not care for it that much. That was in middle school, and being well into adulthood by this point I am very apathetic, even somewhat disgusted by the Switch 2. I will probably never own one, and if I do, it will be second-hand.

It's a shame really, because if there's one thing Nintendo still has going for them, the exclusives for their platform are the best out there. If you know me at all you'll naturally already know that I hate console exclusives, and I'm not going to financially entertain Nintendo for locking good games behind a terrible platform, but I would be lying if I said I wasn't tempted to.

Anyways, going back in time a little bit... When I was very young, I used to routinely wander around the Wii Shop Channel and DSi Shop just to see what was there, looking at all the games I wasn't allowed to have. If there was a free demo of a game, you bet your ass I had already downloaded it and replayed the same intro segment a hundred times just because I could. Kind of like when you got a 5th or 6th gen console without a memory card, so you just played through your games without saving. Annoying, but you dealt with what you had.

Sometimes I was lucky and actually got a game I wanted off of WiiWare. Contrary to what they will tell you, Nintendo has historically been pretty hostile to indie developers. They're still overprotective of their SDK, even now, but it is way better than it was prior to the Wii. WiiWare marks the first step Nintendo took to embracing talented developers with smaller budgets.

Since the Wii's internal flash storage was roughly the size of Chandra Dangi, the games you got off of WiiWare were a lower price and had far less content than the games you'd find on pressed DVDs at the store, so WiiWare was known for having quite a bit of shovelware. That didn't mean there weren't some unique standout titles there, though.

One WiiWare release that always caught my attention was FAST Racing League. For some reason, I never actually bought it, but it's been stuck in the back of my mind for the past fifteen years. Finally pirating the full game after the Shop Channel closed (my Wii was stolen, so I was without one for the final years that the store was still online), I spent quite a bit of time with the game through high school. FAST Racing League is still my favorite game on the Wii, despite having less polished gameplay next to its other racing game contemporaries.

Kind of a silly name for a racing game if I am being honest, very generic-sounding. Yes, FAST is an acronym, and no, it doesn't stand for anything. Don't overthink it.

A Light in the Dark

"Anything is possible."

When I was a kid, just barely playing old PC games on my handed-down Thinkpad T510, frustrated at the large selection of things I could never do with my only home computer, that was my motto. It was part of what drove me to really dig into software engineering and part of why I have a fascination with older computers specifically. Perhaps I took it to an extreme (I would get seriously mad that my dogshit accelerator almost on par with a Riva TNT2 couldn't run a game released the current year), but there was always some truth to the motto nevertheless.

It's not really a secret that I have a soft spot for Shin'en. I proudly wear my inspirations on my sleeves, so I mention them relatively often. What really fascinates me about them though isn't so much the games that they make, as it is the technical marvel that their games demonstrate.

Anyone familiar with Shin'en's history is well aware by now that they have a reputation for, every single time without fail, making such efficient use of Nintendo hardware that they make Nintendo's own first party releases look shameful in comparison. It's no surprise. Shin'en got started as a commercial spinoff to the German demoscene group Abyss, almost thirty years ago. Both Abyss and Shin'en are still around today and thriving as they always have, infact Linzner ("Pink") is still an Abyss member and active in the Commodore Amiga scene. At the time of me writing this, Abyss's latest release is the cracktro "Mobyle" for the A500, just last year. Most triple-A quality studios that see profit don't stay connected to their roots for very long, let alone three whole decades.

Shin'en's games proved over and over again what an ideal game development scenario could look like. What video games could be, when everyone making them is enthusiastic about what they are making, and not hindered by monetary incentives.

This is what every game developer should strive to become.

RTX? What's that?

One of the things about the first FAST game that really stuck with me was its art style. 7th generation Shin'en had a unique aesthetic to their games, that was equal parts stylized cartoon graphics and pseudo-realism. Everything from the sleekly rounded futuristic designs of machinery, to the shockingly good looking special effects, and the "good enough" foilage and nature. It wasn't afraid to be a little weird, but it was still grounded in reality. Their games during this time visually felt like a more modern evolution of something between Treasure's older shmups, dystopian cyberpunk fiction like Minority Report and Deus Ex, psychadelic Bryce 3D terrain renders, and Crytek's Crysis series. It has all of the tact and flavor I like about old computer graphics, plus all the flashy eye candy we craved when we were still young and typical computer hardware was very slow. It was the dream-like illusion of video game realism without ever fully achieving it.

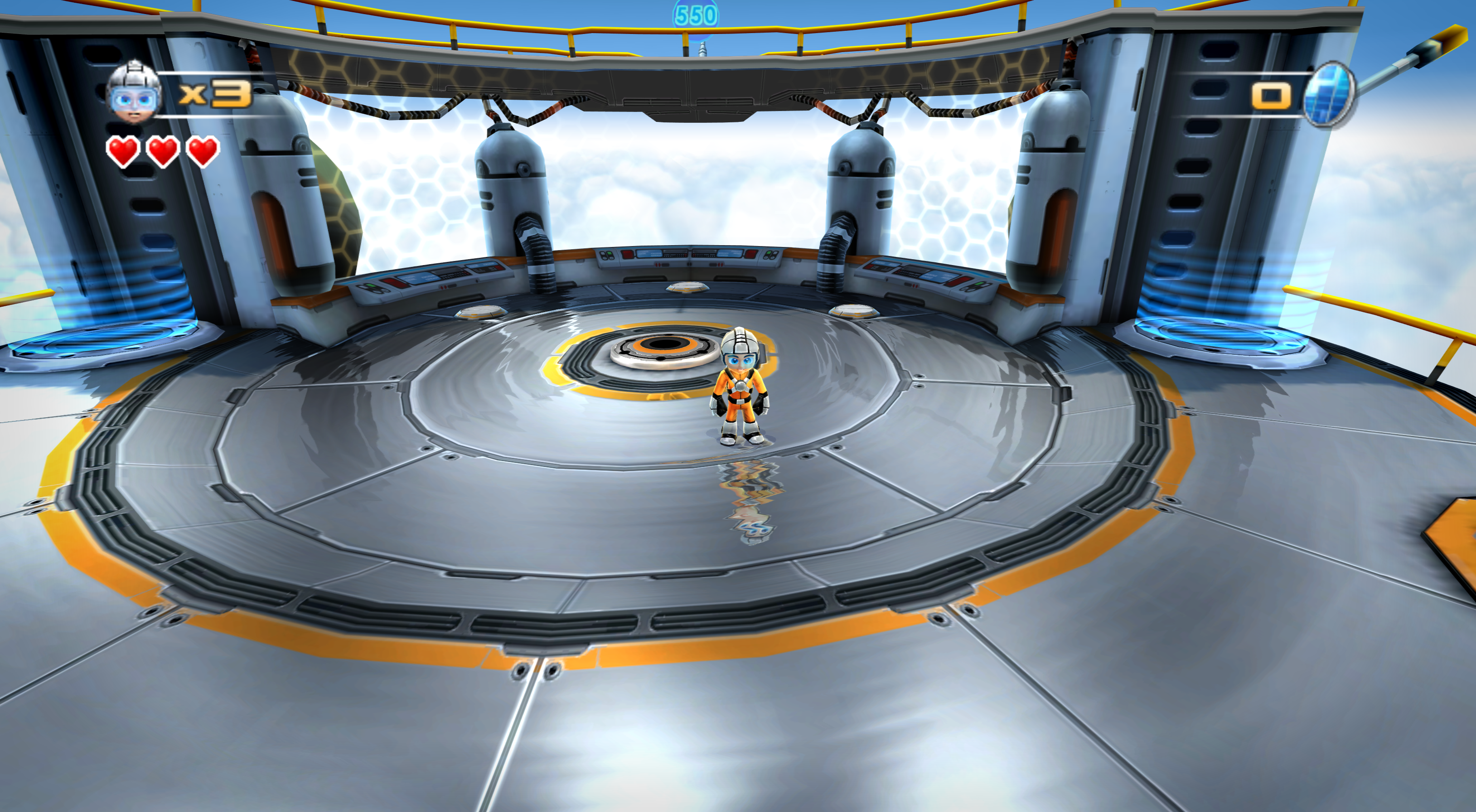

Pictured below is Jett Rocket, a 3D platformer Shin'en released one year before FAST Racing League. It uses the same SHN4 game engine. Here's a good example of one effect Shin'en loved to show off. The game is full of these screen space reflections and they look absolutely gorgeous with the rendering resolution scaled up. On original hardware you only got to see this at 480p, but it ran at a solid 60 FPS and almost never lagged. Remember, this is running on a Wii, which is for the most part an overclocked Gamecube. This is a fixed-function GPU from 2001, crazy stuff!

Here's another screenshot, this one from the game Art of Balance, courtesy of Family Friendly Gaming. Notice the slight reflections on the wooden counter, the refractions through the glass plus-shaped block, and the light rays shining through the window. And Shin'en really loved to use speculars and bump maps everywhere! They're much more subtle in this game but you notice them quite a lot in their work from this era. They seriously did use every single feature of the hardware that they could to do things that most third-party Nintendo developers never bothered to think about. Demoscene expertise at its finest.

Don't Blink

Shift your phase. Win the race. A very barebones premise with deep implications. For those unfamiliar with the FAST series, the main gimmick of all of the FAST games is the phase shift mechanic. Every player ship can swap between a positive and negative charge at will, and to keep up, you have to match the polarity of your ship with the magnetic pads on the track as they change colors. That's prettymuch it.

FAST has always had much less deep movement mechanics than other anti-gravity racing games did. It's a much less technical game than WipEout, and the original Racing League had dead simple controls out of necessity. This makes the FAST series probably the most accessible set of AG racing games skill-wise.

That doesn't mean they're not hard.

I think that Racing League nailed the difficulty in a way that its sequel couldn't quite grasp. Most players familiar with FAST will have only played FAST RMX or the most recently released FAST Fusion, especially since Racing League was never re-released and can't be purchased anymore, so I think it's important to really highlight how different this game was. The biggest difference in the original is that the boost bar was a truly finite resource with major consequences.

A single burst of speed would immediately nuke half the entire tank, and if you were out of boost points you could not change phases. You didn't get to boost just a little to recover from a hiccup if you were low on fuel. There was much less emphasis on trying to maximize boost spam. Instead, the consequence for not filling your boost bar was death. Your boost meter would reset back to 5 out of 10 points if you crashed, so it was up to you if it was worth expending all of your fuel again to make a quicker recovery. On the other hand, you really did not want to crash if you had a good racing line going up until this point.

With simple driving mechanics, it was up to the track design to keep the difficulty in check. You had your more technical tracks like Storm Creek, and your more straightforward ones like the introductory Cove Harbor. What set these tracks apart were mostly the obstacles they would throw right in front of you, and not the opportunities for practicing and perfecting risky stunts.

One of the problems with the way the original Racing League was balanced this way is that its available difficulty options were effectively limited by the Wii's hardware, because as a WiiWare title Shin'en was only barely able to fit 12 full race tracks into the game. The tracks introduced earlier into the game had less replay value than they would in say, WipEout, because the only thing that really changed in each speed class was your required reaction time and there were very little other factors at play.

In a WipEout title, everything about the game would change between speed classes as different tracks demanded different skill sets and had all kinds of different stunts available, to the point where the slower classes were infact actually harder for veteran players who lacked the proper track knowledge at those lower difficulties. This gives WipEout HD and 2048 a significant boost in replay value that FAST Racing League is severely lacking. "Slower" in WipEout was more digestible for new players getting into the game's campaign missions, but it still had a high skill ceiling! I think if Racing League were a physical DVD release, there could've been enough extra content in the game to make up for this.

That's not to say the tracks in Racing League have no replay value. The phase shifting in this first game does a lot to better reward track memorization and a consistent racing line. There are quite a few skip exploits too, so it's a fun game to learn how to speedrun!

Overall, FAST Racing League was very much a technical marvel that could've only happened on the Wii, and its gameplay is indicative of the challenges of creating a good player experience that catered to the Wii's controllers and playerbase. It's one of the very few cases where a game really deserved to be a console exclusive.

It also had a totally killer soundtrack, so that's nice.

Wii Brought U A Sequel

2015 marks the year the old "Shin'en Aesthetic" would be lost in favor of a look more typical for games of the modern era. It was worth it though, because the results absolutely were dressed to impress.

The Wii U was really at its best when a game was designed just for it. Often compared to the Xbox 360, many crossplatform 8th generation games struggled to even function on the damned thing. It was so far behind the competition that SEGA's misguided faith in the platform directly resulted in the monumental embarrassment of a game that was Sonic Boom. Batman Arkham City also comes to mind, infamous for being the laggiest version of the game, only redeemed by its touch controls.

FAST Racing NEO really is the best demonstration of this fact. The Wii U wasn't incapable, but you had to be mindful when developing for it! This game is almost eleven years old now, and it still looks and runs better than every single triple-A Unreal Engine title out there. It really makes me wish we got a PC port of this game, because if this is possible on hardware as slow as a Wii U, imagine how far ahead of its time this game could be when running on the most powerful hardware available now. These are the kinds of games I wish my 4070 could play!

There's no cheap band-aid tricks. No smeary TAA or aggressively noisy bullshit. The game does render at a dynamic resolution, but the speed does a great job of masking what little artifacts there are and it is usually pinned as high as it will go. This is clarity you only usually get in older games.

Orgasmic visuals aside, I much prefer the original Racing League for its gameplay. NEO's design takes a lot more from F-ZERO, with much larger tracks and a serious emphasis on the "FAST" part of its name. The levels are much more fantastical and interesting visually, and the obstacles are of greater variety, but in practice most of the game is designed around trying to spam boosts as much as possible. It's a much less punishing game than Racing League was. There is still a decent skill ceiling, but there is something about the original that is missing here. At least, the newer tracks are much more balanced in difficulty.

One downgrade in NEO is that phase shifting feels a lot more tacked-on, as if its only purpose is to check that you're paying attention. Since phase shifting no longer costs your boost meter, and there's no death traps you have to avoid with the correct phase, it's much less ingrained into the gameplay loop.

The phase shifting in NEO isn't always useless though. One of the techniques carried over from Racing League is the ability to disable jump pads that you're otherwise forced to take. In Racing League this was a crucial, albeit probably unintentional tech, to make more efficient use of the boost meter. Your speed in the first game was severely capped while taking jump pads in order to allow faster speed classes to work smoothly on the smaller tracks. In NEO, some of the tracks intentionally make use of this emergent mechanic, despite the older speed cap no longer being present.

Some other minor mechanics have changed. Start boosting now takes on a more Mario Kart feel as opposed to the single press like in WipEout. Lap boosting and drifting are gone, and you can now strafe like in F-Zero. Getting good at strafing is important for hitting all of the boost pickups and pads. There are some visibility problems due to how aggressively the FOV of the camera changes, with unfortunately no camera settings to tweak, but this is something you overcome as the tracks become more familiar to you. The computer-controlled opponents will rubberband like a real motherfucker, so don't go into this game expecting a casual experience just because the driving mechanics are less overtly punishing.

Since the Wii U was a total disaster in marketshare, Nintendo was ready to put it out of its misery as soon as possible, and rush the Switch out before Microsoft could release Project Scorpio at all costs. Many games like Breath of the Wild intended for Wii U were delayed to make them into Switch games instead. Games already released for Wii U, especially later into its lifespan, would be ported to the Switch not long after. FAST Racing NEO was no exception to this, being re-released as FAST RMX, a launch title for the Nintendo Switch eShop two years after NEO.

FAST RMX is a deluxe edition of NEO with different branding, slightly improved graphics and performance, a couple unique features and all of NEO's DLC included for free. The whole game is a microscopic 1 GB, so it's a no-brainer to install on any friend's Switch incase you forget to bring yours, as on any remotely usable internet connection you can be up and running in merely a few minutes.

Remember, this is running on a cold, quiet Tegra X1 tablet small enough to fit into your cargo pocket. Four years newer than the Wii U, yes, but still more impressive when you consider the form factor and the fact this has to run on batteries.

Looking Towards The Future

I unfortunately won't be able to play FAST Fusion anytime soon. I can't afford a Switch 2, and I am not sure I will be willing to buy one even when I am able to. The Switch was the last Nintendo hardware I put my trust into and that didn't go as planned. Maybe if FAST ceases being a Nintendo exclusive series. We'll see.

The FAST series is very special to me. First it introduced me to a niche subgenre of racing games that most people don't even dare to play (and angry Youtubers will make entire series disrespecting). As I got older, it also proved to me that my time spent honing my programming abilities was going to be worth it. Optimization matters, and your players will definitely notice when you do a good job!

If you own the right hardware, or you're okay with sailing the stormy seas, check these games out. They're fairly decent, if imperfect. At the very least they're a fun novelty and don't take long to Any%, so if you're worried about sinking time into another game you'll never finish, give it a shot anyways.

Anything is possible. Thanks, Shin'en.